With that in mind, the researchers created a second link above ground. “So we wanted, as much as possible, redundancy in this network.”

“But you’re always worried that maybe there’s…some issue that has crept in that you’re not aware of, or something like that,” says David Hume, a researcher at NIST. It’s a well-established method of linking optical clocks at the accuracies scientists want for instance, researchers have built a fiber-optic network connecting clocks across Europe. “We’re lucky that there’s a fiber-optic cable that actually runs under the city of Boulder that connects the clock at JILA to the clocks at NIST,” says Holly Leopardi, a researcher at the University of Colorado, Boulder and NIST. There was already one link between the two sites. The three clocks all work with different atoms: Strontium-87 at JILA, and aluminum-27 ions and ytterbium-171 at NIST. Atomic clocks at different altitudes tick at different rates, thanks to subtle time dilation caused by Earth’s gravity.īoulder, Colorado is fertile ground for linking optical clocks because no fewer than three live there-two at the NIST laboratory and a third about 0.9 miles (1.5 kilometers) away at JILA on the University of Colorado, Boulder, campus. Not only do the clocks themselves operate differently, effects of relativity make themselves known. To show that optical clocks really are the future, scientists need them to be 100 times more accurate than their cesium-microwave predecessors-a benchmark they hit in this new study.īut they also need different timepieces around the world to agree on the time, especially because not all optical clocks use the same atoms. The latest cesium clocks are accurate to within a millionth of a billionth of a second. Because light has higher frequencies than microwaves, and thus shorter periods, you can use that light to get much more accurate timing.

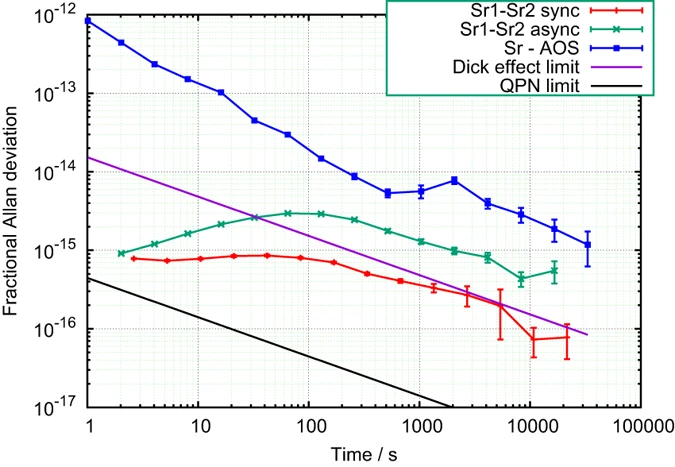

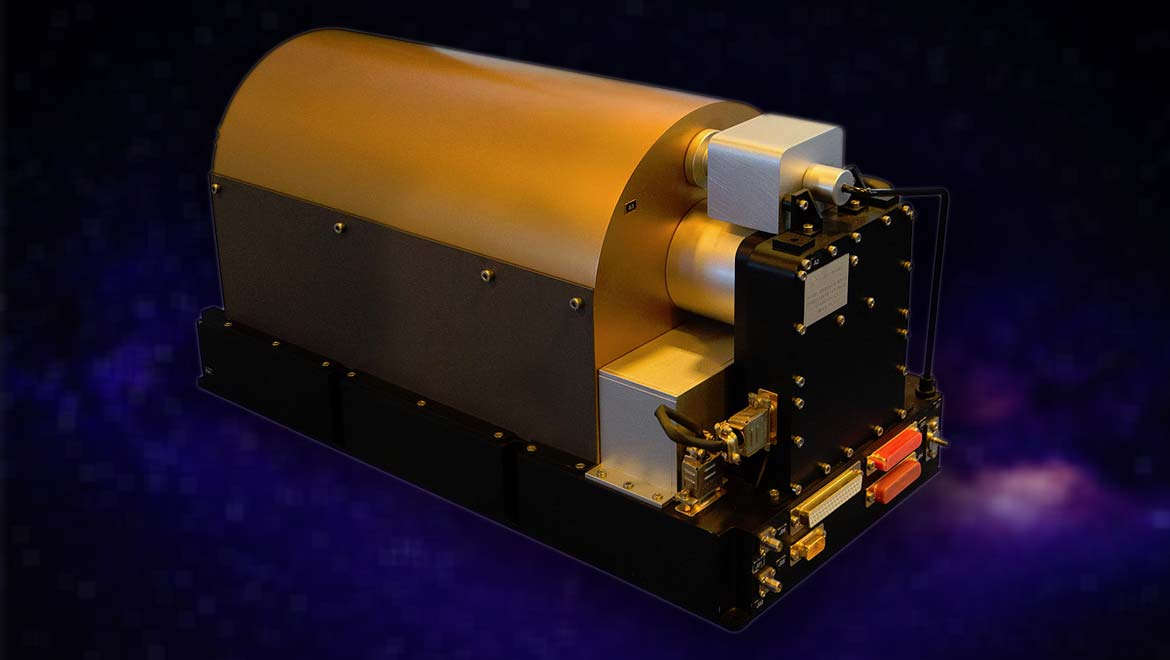

BACON and other projects are tinkering with a much newer type of atomic clocks, called optical clocks, which rely on light. That sounds impressive, and it is-but it’s Cold War-era tech. To wit, exactly 9,192,631,770 of those periods make up one second. You can use the period (the time between the peaks of a wave) of those microwaves to keep time. In particular, we look at the frequency of the photons that are absorbed and emitted when electrons shift energy levels, which in a cesium-133 atom are microwaves. Today, we define the second with atoms-in most cases, cesium-133. BACON’s measurements, recently published in Nature, are around 100 times more accurate than even the ultra-accurate atomic clocks that the planet’s official timekeepers use today.

By linking different clocks, researchers can check to make sure they’re all reliably keeping time.Īnd once that can happen, it paves the way for this newer, more accurate type of clock to redefine the second. In fact, the second’s definition hasn’t changed since 1967.īut now, dozens of researchers in Boulder, Colorado, working together in the Boulder Atomic Clock Optical Network (BACON), have been able to connect three of the world’s most accurate clocks together in a critical step towards creating a new definition. While most of the standard SI units were redefined in 2019, the second wasn’t one of them. That’s partly because creating ever more accurate clocks enables scientists to better define the second, our base unit of time. And since systems like GPS rely on timing signals, they could unlock a new generation of navigation technology. They also help geodesy, the science of measuring the Earth itself, allowing us to map its gravity, its surface, and its sea floor to within centimeters. Better clocks could fine-tune researchers’ ability to measure relativity and dark matter. It might seem trivial to bother improving a clock that’s already so accurate, but it’s crucial for a few areas of science. But at the bleeding edge of timekeeping, scientists are fine-tuning clockwork that might stray no more a second over the course of billions of years. A towering pendulum clock loses or gains around a minute every month, while the quartz in a digital watch stays within a few seconds.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)